This morning, while teaching (a seminar on 'Social Justice and Inequality' appropriately enough), one of my students suddenly interrupted and said 'Could I just make an announcement: Eric Hobsbawm has just died'. I had mixed initial emotions - impressed that a first year politics student knew of Hobsbawm and understood it was a significant enough event to interrupt the class, slight irritation and disappointment that the aforementioned student was clearly not paying full attention to the seminar discussion and was checking his phone - and, above all, I guess sadness that the inevitable had happened and

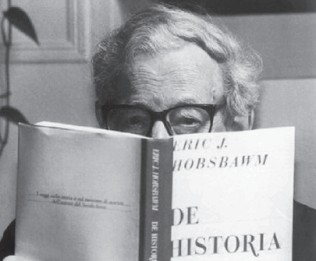

Eric Hobsbawm - one of the greatest Marxist historians of the 'short twentieth century' and a towering figure perhaps almost unique in his range of concerns, breadth and depth of knowledge and command of sources - was no longer with us.

I only met Hobsbawm very briefly on one occasion - when he was speaking alongside Dorothy Thompson and John Saville at the launch of Saville's

Memoirs of the Left in London almost a decade ago - but, ever since one of my history teachers at school had kindly photocopied an interview with Hobsbawm from the

Guardian c mid-1990s for me because of my interest in Marxism, like many many others, his writings on Marxism, history and the responsibility of historians in society have been a massive influence. The 1978 interview with Hobsbawm by Pat Thane and Elizabeth Lunbeck from

Radical History Review provides one of the best short introductions to his life and work. 'It seems to me that it is very important to write history for people other than pure academics', Hobsbawm noted in that interview. 'The tendency in my lifetime has been for intellectual activity to be increasingly concentrated in universities and to be increasingly esoteric, so that it consists of professors talking for other professors and being overheard by students who have to reproduce their ideas or similar ideas in order to pass exams set by professors. This distinctly narrows the intellectual discipline...the kind of people one aims at are, I hope, a fairly large section of the population - students, trade unionists, plain ordinary citizens who are not professionally committed to passing examinations but do want to know how the past turned into the present and what help it is in looking forward to the future'.

This healthy approach was shaped by Hobsbawm's commitment to politics and his leading role in the Communist Party Historians Group (and its successor groups) - which avoided what he saw as the 'danger' of Marxist history being about just labour history in the 19th and 20th centuries and instead 'had people who dealt with everything - classical antiquity, medieval feudalism, the English revolution.' After beginning with the Fabians (on which he did his PhD), Hobsbawm did write some classic works on the modern labour movement like

Labouring Men and

Worlds of Labour but also wrote an extraordinarily wide range of topics, - from primitive rebels and social bandits like 'Robin Hood', to jazz (under the pseudonym 'Francis Newton') and 'Captain Swing' (an English agricultural workers rebellion), to his famous quartet on modern world history

The Age of Revolution,

The Age of Capital,

The Age of Empire and

The Age of Extremes. His orthodox Communism - which led later to an embrace of what was becoming New Labour - and becoming

'Neil Kinnock's favourite Marxist' - meant parodoxically politically he was weak despite his generally outstanding strengths as a historian. As

Chris Harman noted in 2002 - reviewing Hobsbawm's autobiography

Interesting Times, 'there might be two Eric Hobsbawms. One ended his book on the 20th century,

The Age of Extremes,

by describing the system as out of control and threatening all of

humanity. The other was at that very time praising New Labour’s approach

to politics....there is the Hobsbawm who still calls himself a Marxist, who wrote

Labouring Men and

The Age of Revolution,

is scathing about the revisionist and postmodernist historians, is

damning about the Blair government, and still insists on left wing

political commitment. But there is also the Hobsbawm who backed the Labour right against

Tony Benn, told us the poll tax could never be beaten, extolled the

Italian Communist Party’s cosying up to the Christian Democrats, and

sponsored the

Marxism Today gang as they galloped towards a political yuppieland of interviews with Tory ministers and columns in the Murdoch press.'

In particular, if while as a member of the Historians Group of the CPGB, twentieth century history was impossible to write, even when Hobsbawm did come to write the history of the twentieth century in

Age of Extremes, his famous thesis about

'The Forward March of Labour Halted' meant he did not focus on the possibilities presented by

working class struggles. (There were other surprising omissions in

Age of Extremes, such as the lack of mention of the struggles for black liberation in the US and even figures such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X are absent - and this from a jazz enthusiast and pioneering jazz historian (!) - though this is perhaps understandable given Hobsbawm was writing a quite personal account of the century late on in his career rather than a 'total history'). Yet for all his limitations, ever since Hobsbawm joined the Communist movement in the early 1930s as a

young Jewish socialist activist who decided to embrace the future rather than no future as Hitler's Nazis seized power in Germany - at possibly the darkest moment in the history of the century - up until his recent intellectual defence of Marx and Marxism in

'How to Change the World', his voluminous intellectual work over the course of his life represent a colossal, immense contribution to not only historical scholarship in general and Marxist scholarship in particular - but also a resource of hope that future generations can draw upon in the struggle for a socially just and equal world.

I will add obituaries and tributes etc as and when I get time:

Guardian obituary

Ian Birchall in

Socialist Worker

Paul Blackledge in

Socialist Review

Neil Davidson for New Left Project

Mark Mazower in the

Guardian

Mark Steel in the

Independent

Ramachandra Guha in

Prospect

David Feldman

Eric Foner in

The Nation

Matthew Cole

for Verso.

Marc Mulholland in

Jacobin

Tristram Hunt in the

Telegraph and

Guardian

Evan Smith on Hobsbawm and '1956'.

Donald Sassoon on

Open Democracy

Keith Flett for the London Socialist Historians Group

David Morgan and the

Socialist History Society

See also

Daniel Pick,

Ishan Cader,

Nicholas Jacobs

and

Jonathan Derbyshire

Listen to Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History

Articles in Past and Present

Making History interview

Edited to add: To take up and challenge all the points raised by the rabid but predictable anti-Communist attacks on Hobsbawm that have appeared over the last day or so from critics ranging from the Right to the 'pro-war Left' would be a true 'labour of Sisyphus', but perhaps the very worst and most disgraceful I have seen so far comes from

A.N.Wilson in the

Daily Mail. Wilson - who might want to reflect on how his last book

about Hitler

was received by

historians

of Nazi Germany (see for example

Richard

Evans in the

New Statesman) before accusing anyone of writing 'badly written' books as he does of Hobsbawm, has penned perhaps the most appalling and

insulting attempt at character assassination to date. He does not pause a moment to pay even the most begrudging of respects but launches straight in: 'He hated Britain and excused Stalin's genocide but was hero of the BBC and the

Guardian Eric Hobsbawm a TRAITOR too?' Wilson makes the slanderous accusation that Hobsbawm was a Soviet agent on the grounds that 'he was at Cambridge during the thirties and knew Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess and other Soviet agents', and because he later wanted to read his MI5 file to find out who had 'snitched on him'.

This is it in terms of 'evidence', but who needs 'evidence' when you are A.N. Wilson writing in the

Daily Mail and so can get away with inferring from this that therefore Hobsbawm must 'have done something of which the authorities were entitled to take a dim view - possibly something actively criminal'. Hobsbawm was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain - ipso facto the authorities were going to be taking a 'dim view' of anything he did - actively 'criminal' or not. Yet, the fact Hobsbawm was a political refugee in Britain, was a historian, and was a well known member of the CPGB means he would have been possibly the worst and most useless person for the Soviet Union to have had as an agent on lots of counts, and Hobsbawm's remark seems to have been a perfectly innocent inquiry into which individual was spying on him on behalf of the British state. Wilson also accuses Hobsbawm of 'openly hating Britain' - and there are certain things Hobsbawm probably did 'openly hate' about

Britain - its Empire and British imperialist crimes abroad for example, or the racism and anti-semitism at home that he would have encountered as a Jewish refugee from

Nazism during the 1930s. Such anti-semitism came from groups like the British Union of Fascists and

newspapers who supported the Blackshirts like the er,

Daily Mail (who were also cheering on Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in this period). Yet one only needs to glance at Hobsbawm's voluminous writings on labour history and working class political traditions and culture to give the lie to the idea that Hobsbawm 'hated' British working class people. As to Wilson's final suggestion that 'Hobsbawm himself will sink without trace...his books will not be read in the future' - well, while historians are not in general in the business of making predictions, I think this is one prediction that almost every historian can safely say will be proved wrong. Whether anyone will read or remember A.N. Wilson after his passing is a far more open question...

Edited to also add: I wrote too soon - you can get even worse than Wilson - see

this Spectator piece by the poisonous

Douglas Murray.

Labels: history, Marxism, New Labour, socialism